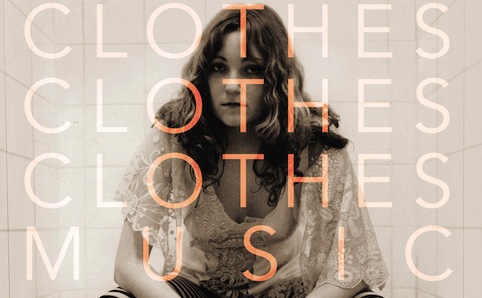

Viv Albertine

TIME OUT: 2014

A punk history on the surface, the memoir of the former Slits guitarist is more a story of survival.

When Viv Albertine’s manager said she shouldn’t write her own book, it must have brought back some memories. In 1976, when Viv joined punk band the Slits, the majority of women on the scene contented themselves with being hangers-on, rather than be trusted to do the job themselves. Inspired by Jenny Fabian’s book, Groupie, Albertine idly considered becoming one herself, before Keith Levene taught her to play guitar. She’d scour the back of album sleeves for the names of girlfriends and wives, and emulate the way they dressed. As a scene in her book with Johnny Rotten will attest, though, she wasn’t quite up to scratch with blowjobs.

London in the 1970s was uninspiring and hostile, and in response, Clothes, Clothes, Clothes, Music, Music, Music, Boys, Boys, Boys is a deliberately unfeminine, unflattering account of Albertine’s life. She and her friends grew up poor, malnourished and practising poor personal hygiene: “faces as pale and grey as mushrooms poking out of the dirt”. They threw themselves into following the disaffected punk scene because the bands were fronted by real people – people from the estates of North London, like them.

While at Hornsey School of Art – whose alumni includes Adam Ant and Ray Davies – Albertine spent a spell in the Flowers of Romance before her friend Sid Vicious fired her. It had surprised her that he’d wanted to form a band in the first place, as men rarely enlisted women.

“Sid was intelligent and open-minded,” she reflects to Time Out Melbourne. “He saw things other people didn’t see. He was an opportunist, always alert for an idea or an adventure; I could see the thought occurring to him almost as he was forming the words. Also, I looked great – spiky peroxide-blonde hair, leather jeans, DM boots, stripy T-shirt, leather jacket… the way I was dressed helped Sid see me as androgynous.”

Albertine floated around for a bit before gravitating toward the Slits – who wondered why she’d taken her time. She hadn’t intended to join an all-girl band, but the Slits weren’t daggy and corny like the girl groups that had gone before.

“No girl bands existed except the Runaways,” she says. “I was aware through reading the music press that they were put together by Kim Fowley. They were very manufactured and their songs were all jailbait orientated with the singer in a corset. I didn’t buy it. And then there was Fanny, who were like a bunch of blokes. So there was no one to admire, no role models.”

Albertine, Ari Up, Palmolive and Tessa Pollitt were vastly different in temperaments, but just like the Clash (whose guitarist Mick Jones was in an on-off relationship with Albertine for years), they became a tight gang.Clothes… is peppered with alarming accounts of being cornered by gangs and groped by random men, so walking four abreast down the street with the Slits with matching backcombed hair felt liberating.

“It was all still very 1950s – men actually thought it was their right to touch you without asking and did so all the time,” Viv recalls. “Together we felt invulnerable – a very new feeling to a girl at that time. We were all so committed to each other that we would have fought to the death if we had to, to protect one another. We felt like our own little tribe. It was very threatening for men, because they could see we were challenging their role in society – and they did everything they could to stop us, from being violent to ridicule.”

On an individual basis, the band members had a fraught relationship. In particular, Albertine’s feelings waxed and waned towards singer Ari Up, who was just 14 when the band started, and who gleefully copped the majority of the abuse from the audience. Ari had an unnerving way of studying and emulating people, from the boys skanking at reggae clubs to Albertine’s manner while booking gigs on the phone. It was as though she were building herself, brick by brick. Similarly, Albertine assimilated the qualities she admired in older women, such as Yoko Ono, activist Caroline Coon, Vivienne Westwood, and Ari’s mother (and John Lydon’s wife) Nora Foster, who didn’t stop working just because she’d had a child.

The Slits went on tour with the Clash and found some notoriety in the music press, but were too unapologetically loud and confrontational to be on TV much – not in an era when Legs & Co. were a popular dance troupe on Top of the Pops. So was the idea of fame and financial success completely inconceivable?

“It was to the Slits, but I’m not so sure about the male bands at the time,” she says. “I think they were more careerist about it than we realised. The Slits were on a mission to change the world for girls and therefore change it for boys as well. We were absolutely driven to do something different musically and culturally.”

It made no sense to Albertine to try and sound like male guitar players, so instead of aping Led Zeppelin as it seemed every other kid did when learning the ropes, she tried to mimic animal noises, ignoring chords, scales and traditional structures. It’s a style that has influenced all-girl bands L7 and Warpaint in later years.

“The reason boys are in the title of the book is because when I was young boys did all the good stuff, all the interesting stuff – I wanted to be a boy,” she says. “And not because of penis envy – Freud got that wrong – but because of their opportunities. They were in bands, they hitchhiked round the world, they were the doers. Women were ignored. It sounds terrible to say now, but boys and men were much more interesting than women. Now it’s the other way around.”

In 1982, the band split up shortly after making their second album, Return of the Giant Slits. Albertine studied film and went on to become a director, at which point she met her husband and everything changed.

While Clothes… will be ravenously consumed by anyone who owns Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming or Caroline Coon’s The New Wave Punk Rock Explosion, the now 59-year-old Albertine says she’s not interested in rehashing the past and doesn’t read other bios of the era. “I only wrote about it because I wanted to write about the second half of my life,” she says.

Albertine’s life did a dramatic 180, as she moved with her husband to a dream house in the seaside town of Hastings, and buried her past as a Slit in favour of being an obedient wife – happily, at first.

“I was exhausted, burnt out, from years of being on the streets, in the music industry, attacked, having to front it out, stand up and fight, being misunderstood, ridiculed… I was knackered mentally and emotionally,” she says. “I’d sought a family and a home like a safe harbour. I also hadn’t thought, in my militant way, that maybe family and love were important. Those subjects were not raised in early feminism – they couldn’t be.”

Unfortunately, Albertine and her husband were in for a harrowing journey as they embarked on a long and bloody course of IVF treatment, resulting in miscarriages and disappointments. When Albertine finally did give birth to a daughter, she found out shortly after that she had cervical cancer. She eventually emerged from it all with her body a battlefield, something to be reclaimed. But Viv from the Slits had disappeared entirely from view, and her relationship with her husband was in tatters.

The emancipation began with sculpting and led to picking up the guitar again, and driving for up to three hours to open mic nights to stand grimly in front of a mostly male audience, playing songs as a middle-aged mum.

“Women can be perfectionists and it’s crippling,” she remarks. “The culture of constantly assessing yourself physically absorbs into your mind and you apply it to everything you do. Possibly patriarchal society has added to this by over criticising women to keep them down – it certainly happened to the Slits and it happened to me again in my marriage. But women have to be okay with failing and making mistakes.”

Filmmaker provocateur Vincent Gallo got in touch, determined to meet one of his fantasy women, and a trip to New York resulted in meetings with both him and Ari Up’s new version of the Slits. Albertine wasn’t entirely won over by either encounter, but they proved to be the impetus she needed to leave her marriage and start again.

With encouragement from bands including the Raincoats and Warpaint, she started releasing new material, working with some of her all-time favourite bassists, Jah Wobble and Tina Weymouth among them. While the Slits’ 1979 song ‘Typical Girls’ had railed against stereotypes put upon young women, Albertine’s 2013 offering, ‘Confessions of a MILF’, about the limitations put on wives and mothers, could almost be the update.

When asked about where her music may take her, Albertine retorts, “Everyone wants to know about future plans, like you should always have a goal. I am an advocate of fallowness and dry periods and voids. That’s where new ideas come from, even if those creative droughts are years long. I think they should be celebrated and encouraged. The young are too goal orientated; they need to play more. We don’t need everyone to be churning out derivative work all at the same time.”

With the close of the book reflecting on the loss of Ari Up from cancer in 2010, Albertine admits that she was more inspired by the fiery younger woman than she ever led on. And number one on Albertine’s agenda now, one suspects, is to be an inspiration to her teenage daughter.